The RMS Titanic, a behemoth of steel and ambition, was more than just a passenger liner; it was a potent symbol of Edwardian progress, a testament to human ingenuity, and a floating palace that epitomized luxury and supposed invincibility. Its maiden voyage in April 1912 was heralded as a triumph, a seamless journey into a future where technology reigned supreme. Yet, this narrative of assured progress was brutally shattered in the early hours of April 15th, when news spread across the globe that the "unsinkable" Titanic had succumbed to the icy embrace of the North Atlantic. The sinking sent shockwaves through the world, a stark reminder of humanity's vulnerability in the face of nature's power and a tragedy that continues to captivate and horrify over a century later. This article will delve into the minute-by-minute unfolding of this catastrophic event, explore the depths of the human tragedy, and examine the immediate aftermath that left a world grappling with disbelief, grief, and a fundamental reassessment of maritime safety.

|

| The RMS Titanic colliding at 11:40 PM with the fateful iceberg (personal work) |

The Fateful Encounter: A Whisker Away from Disaster in a Tranquil Sea

The afternoon of April 14, 1912, unfolded with an air of deceptive serenity aboard the Titanic. The ship, under the command of the experienced Captain Edward Smith, was making excellent progress towards New York, having covered a significant portion of its transatlantic journey. However, the day had been marked by a series of ice warnings transmitted by other vessels in the area, reporting large icebergs and ice fields along the Titanic's intended route. These warnings, while received by the ship's two wireless operators, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, were not all promptly relayed to the bridge or given the level of attention that hindsight suggests they warranted. Some messages were reportedly stacked up or misplaced amidst the operators' heavy workload of transmitting passengers' personal messages.

|

| Titanic nearing the ice field at approximately 11:35 P.M. Art by Ken Marschall |

As night descended, the atmospheric conditions contributed to the unfolding tragedy. The sea was unusually calm, lacking the telltale whitecaps that typically break around icebergs, making them harder to spot. The sky was clear and filled with stars, but a slight haze on the horizon further reduced visibility. The temperature had dropped significantly, hovering just above freezing. At 11:40 PM (ship's time), lookout Frederick Fleet, stationed in the crow's nest, his eyes straining in the darkness, suddenly saw a colossal iceberg looming directly in the ship's path, a dark mass against the starlit sea. He frantically rang the warning bell three times and telephoned the bridge, uttering the now-famous words, "Iceberg right ahead!" First Officer William McMaster Murdoch, on duty, reacted instantly. He ordered Quartermaster Robert Hichens at the helm to "hard-a-starboard," a command to turn the ship sharply to port (left), and simultaneously ordered the engine room to put the engines "full astern" in an attempt to slow the vessel's forward momentum. As maritime accident analyst Samuel Halpern meticulously reconstructs in Report into the Loss of the SS. Titanic: A Centennial Reappraisal (2011, p. 105-110), the time between the sighting and the collision was agonizingly short, likely no more than 30 to 40 seconds. Despite Murdoch's swift actions, the Titanic, traveling at approximately 22.5 knots (around 26 miles per hour), could not turn sharply enough to completely avoid the massive iceberg. The ship's starboard side scraped against the submerged portion of the iceberg for several seconds, tearing a series of holes below the waterline across at least five of its supposedly watertight compartments.

The Realization of Disaster: A Gradual Awakening to Mortal Danger

The immediate aftermath of the Titanic's collision with the iceberg was characterized by a deceptive stillness on the upper decks. Many passengers, particularly those in first class, felt little more than a slight shudder or a momentary pause in the ship's engines. Some were jolted awake in their cabins, while others remained undisturbed, attributing the sensation to a large wave or a minor technical issue. Survivor First Class Passenger Elizabeth Shutes recalled, "We just felt a little jar, as if we had gone over a big wave. Some of us laughed" (as quoted in Titanic: Women and Children First by Judith B. Geller, 1998, p. 45). This initial lack of obvious chaos contributed to a widespread underestimation of the severity of the situation.

On the bridge, however, the atmosphere was one of immediate concern. Captain Edward Smith, having been promptly informed of the collision by First Officer Murdoch, arrived quickly and took command. His initial actions were decisive: he ordered the engines stopped and instructed Murdoch to ascertain the extent of the damage. Simultaneously, he summoned the ship's carpenter, John Hutchinson, to sound the ship for water ingress. This involved checking the sounding wells in the lower compartments to determine if any were taking on water.

|

| James Cameron Titanic´s (1997) |

Below decks, the reality of the situation was unfolding with alarming speed. Chief Engineer Joseph Bell, alerted by the engine telegraphs indicating "stop," was already investigating the cause. The impact had been felt more acutely in the engine and boiler rooms, with some firemen reporting a sudden rush of air and the sound of escaping steam. As the carpenter and engineers began their inspections, they encountered a chilling sight: water was pouring into several compartments along the starboard side, rising rapidly. In the mail room on G Deck, postal clerks were wading through ankle-deep water, frantically attempting to move mailbags to higher ground as the icy seawater continued to flood in. This dramatic scene, recounted by survivor Postal Clerk Oscar Scott Woody (U.S. Senate Inquiry, p. 188-190), starkly illustrated the speed and severity of the breach in the hull.

Crucially, Captain Smith sought the expert opinion of Thomas Andrews, the managing director of Harland and Wolff, the Titanic's builders, who was on board for the maiden voyage. Andrews, with his intimate knowledge of the ship's design and construction, conducted a thorough inspection of the damaged areas. His assessment was swift and devastating. He determined that at least five watertight compartments had been breached, exceeding the ship's capacity to remain afloat. As historian Richard Davenport-Hines notes, Andrews' calm but grave pronouncement to Captain Smith – that the ship had only about an hour or two before it would sink – marked the definitive moment when the realization of the impending disaster took hold among the senior officers (1998, p. 170).

As the senior officers grappled with this grim prognosis, the news of the collision and the subsequent flooding began to filter through the crew. Orders were issued to various departments, though initially, there was an effort to maintain calm and avoid alarming the passengers. However, the sight of water rising in the lower levels and the sound of the ship's pumps working at full capacity conveyed a sense of urgency to those below decks. Leading Fireman Frederick Barrett, who was in Boiler Room No. 6 when the iceberg struck, described the terrifying experience of water rushing in and the subsequent orders to evacuate that room (British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry, Question 1724-1755).

|

| A night to remember film (1958) |

On the upper decks, passengers remained largely unaware of the true danger for a significant period. Rumors began to circulate – some suggested a minor collision with another vessel, others speculated about a propeller malfunction. However, as time passed and the ship remained stationary, an unusual occurrence for a vessel of the Titanic's stature, a sense of unease began to spread. Passengers noticed subtle signs: the engines were silent, the ship had a slight list, and crew members were moving with a sense of urgency that belied their attempts to appear calm. The venting of steam from the ship's boilers, a loud and sustained hissing sound, became noticeable to those on deck and served as an early, unsettling indication that something was seriously wrong with the ship's machinery. Survivor Second Class Passenger Kate Buss recalled, "We went out on deck to see what had happened, and they told us we had just touched an iceberg, but it didn't seem anything serious. Then we saw the steam escaping, and we knew it must be something more" (as quoted in Titanic: The Official Story by Michael Davie, 1986, p. 78).

The realization of the disaster was not a sudden, dramatic event for most passengers but rather a gradual awakening to the mortal danger they faced. The initial disbelief and complacency slowly gave way to a growing sense of anxiety and fear as more time passed, the ship's list became more pronounced, and the crew began to instruct passengers to put on their lifebelts. This period of transition, from the initial shock to the undeniable awareness of the impending catastrophe, was crucial in shaping the psychological responses of those on board and set the stage for the chaotic and ultimately tragic events that would follow

|

| Titanic sinking by the bow. Art by ken Marshall |

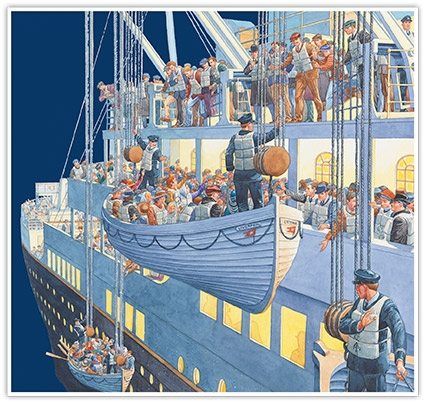

The Order to Abandon Ship: A Heartbreaking Calculation of Loss

As the inexorable inflow of water became undeniable and the forward tilt of the ship became subtly perceptible, Captain Smith, after consulting with Thomas Andrews and his senior officers, made the agonizing decision to order the abandonment of ship. The time of this crucial order is generally placed around 12:20 AM on April 15th, approximately 40 minutes after the collision. The process of preparing the lifeboats began with a degree of order, guided by the maritime tradition of "women and children first." However, the stark reality of the Titanic's insufficient lifeboat capacity quickly became apparent. The ship carried only 20 lifeboats and four collapsible boats, totaling enough space for just 1,178 people, while there were over 2,200 souls on board.

|

| National Geographic Kids |

This critical shortage was a consequence of outdated regulations that based lifeboat capacity on ship tonnage rather than the number of passengers, coupled with a prevailing belief in the Titanic's inherent unsinkability. Survivor First Class Passenger Marian Thayer vividly described the scene on the boat deck, recalling, "There was very little excitement at first, but a sort of quiet determination. The officers were calling for women and children, but many of the women refused to leave their husbands" (as quoted in Titanic: A Night Remembered by Stephanie Barczewski, 2004, p. 88). The loading of the lifeboats was a slow and often chaotic process. Some boats were lowered with empty seats, due to a combination of reluctance from passengers and misjudgments by the officers in charge. Other boats were filled closer to their capacity. Stories of heroism and tragedy unfolded at the lifeboats: husbands bidding farewell to their wives, families being separated, and officers making difficult decisions about who would be allowed to board.

The Sinking: The Final, Terrifying Descent into the Abyss

As the minutes ticked by after the order to abandon ship, the Titanic's condition steadily worsened, the subtle list to starboard gradually transforming into a pronounced tilt that made movement around the decks increasingly difficult. Passengers and crew alike struggled to maintain their footing on the sloping surfaces, the once-grand promenade now an obstacle course. Survivor First Class Passenger Jack Thayer vividly recalled the increasing angle, stating, "The ship was now tilting slowly but surely to starboard. Everything movable was sliding slowly to the starboard side" (A Survivor's Tale, 1940, p. 57). The elegant furniture in the lounges and staterooms began to shift and slide, adding to the growing sense of chaos and danger.

The ship's electrical power, a symbol of its modernity and luxury, began to falter. Lights flickered intermittently, casting eerie shadows across the increasingly panicked faces of those on board. This visual instability amplified the growing fear and uncertainty. Then, in stages, sections of the ship plunged into darkness, the grand staircases and opulent public rooms becoming black voids. The loss of light not only disoriented those still on board but also extinguished a vital beacon of hope for any potential rescuers in the distance.

|

| 3D recreation by Titanic: Honor and Glory |

Accompanying the visual decline were terrifying sounds emanating from the very structure of the ship. The immense pressure exerted by the encroaching water caused the steel plates to groan and creak under the strain. As the angle of the ship steepened, these groans intensified into loud, wrenching sounds, like a giant beast in its death throes. Survivor Second Class Passenger Lawrence Beesley described the horrifying symphony of the sinking, recalling "a dull, muffled roar which seemed to come from the very bowels of the ship. It was not a sudden explosion, but rather the tearing apart of some great structure" (The Loss of the SS. Titanic: Its Story and Its Lessons, 1912, p. 68). The crashing of unsecured objects within the ship, the shattering of glass, and the relentless roar of water surging through the decks created a terrifying auditory landscape of destruction.

Around 2:18 AM, the unbearable stress on the Titanic's hull reached its breaking point. The ship, now tilted at a severe angle with its bow deeply submerged, fractured between the third and fourth funnels. This catastrophic event, initially debated by survivors but later confirmed by the discovery of the wreck, was accompanied by a deafening roar. Survivor Third Class Passenger Catherine McGowan recounted, "There was a terrible crash, and the ship seemed to break in two right before my eyes" (as quoted in Titanic: The Last Night of a Small Town by John Welshman, 2012, p. 158). The forward section of the ship, now heavily laden with water, plunged rapidly beneath the surface, likely creating a powerful suction that pulled some individuals down with it.

|

| National Geographic |

The stern section, momentarily relieved of the immense weight of the bow, remained afloat for a short period, rising almost vertically out of the water, its propellers spinning uselessly in the air. This dramatic spectacle, illuminated by the remaining lights on the stern, was witnessed by many in the lifeboats and those still struggling on the debris-strewn surface. Survivor Second Officer Charles Lightoller, who was swept into the water from the bridge, described the surreal sight of the stern towering above the waves before it too began its final descent (Lightoller, 1935, p. 128). The stern then slowly sank, disappearing beneath the icy waves at approximately 2:20 AM, marking the final plunge of the once-magnificent Titanic into the abyss.

|

| Titanic final seconds. 3D recreation by Titanic: Honor And Glory |

The immediate aftermath was a scene of unimaginable horror. The dark, frigid water was filled with debris – pieces of wooden decking, furniture, and luggage – and hundreds of people struggling desperately for survival. The temperature of the water, a mere 28 degrees Fahrenheit, was lethal, and hypothermia would claim most of those who were not in lifeboats within minutes. The silence of the ocean, after the cacophony of the sinking, was broken by the heart-wrenching cries and screams of those in the water, a chorus of despair echoing across the dark expanse. Survivor Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall, who was in charge of Lifeboat No. 2, testified to the agonizing sounds, stating, "It was the most terrible sound I have ever heard, the cries of hundreds of people struggling in the water, and they gradually died away" (British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry, Question 5304).

Throughout these final, terrifying moments, amidst the chaos and the unfolding tragedy, there were also acts of remarkable bravery and selflessness. The ship's band, led by Wallace Hartley, famously continued to play music on the boat deck, their melodies providing a semblance of calm and solace to those facing their final moments. While the exact last tune they played remains debated, many survivors recalled hearing "Nearer, My God, to Thee." Their unwavering performance in the face of certain death has become a legendary testament to human courage and dignity.

The final descent of the Titanic was not a swift, clean sinking but a protracted and agonizing process marked by structural failure, the loss of vital systems, and the terrifying cries of those caught in its grip. The vivid accounts of survivors, pieced together over the years, paint a harrowing picture of the ship's last moments, a testament to the sheer scale of the disaster and the profound human tragedy that unfolded in the icy darkness of the North Atlantic.

|

| The bow section of the Titanic hitting the seabed |

The Human Tragedy: A Tapestry of Loss and Enduring Stories

The sinking of the Titanic resulted in the deaths of 1,517 people, a staggering loss that profoundly impacted families and communities worldwide. The human tragedy encompassed a wide spectrum of individuals, from the wealthiest members of society to impoverished immigrants seeking a better life in America. The stark disparities in survival rates highlighted the social inequalities of the time. Approximately 63% of first-class passengers survived, compared to only 24% of third-class passengers. Women and children were prioritized in the lifeboats, resulting in a survival rate of around 74% for women and 52% for children, while only about 20% of men survived. Yet, within these statistics lie countless individual stories of courage, love, and sacrifice. Captain Edward Smith's dignified acceptance of his fate, Chief Engineer Joseph Bell's unwavering dedication to his duty, and the band's final performance are just a few examples of the heroism displayed in the face of death. Stories of families torn apart, of selfless acts of assistance, and of the agonizing choices made in those final hours continue to resonate. Survivor First Class Passenger Kate Gold recalled the bravery of her husband, who ensured she and their daughter were safely in a lifeboat before returning to the sinking ship (as recounted in Shadow of the Titanic by Andrew Wilson, 2011, p. 188). The human tragedy of the Titanic is not just a number; it is a collection of individual lives cut short, each with their own hopes, dreams, and stories.

The Immediate Aftermath: A Cold Dawn and the Arrival of Rescue

In the pre-dawn darkness, the survivors in the lifeboats, huddled together for warmth and battling the effects of shock and exposure, awaited the arrival of rescue. The RMS Carpathia, under the command of Captain Arthur Rostron, having received the Titanic's distress calls, had steamed through the night at full speed, navigating treacherous ice fields to reach the scene. Arriving around 4:00 AM, the Carpathia began the slow and painstaking process of taking the survivors on board. Survivor Third Class Passenger Anna Sofia Sjöblom described the immense relief upon seeing the lights of the rescue ship, stating, "It was like a miracle, a light in the darkness" (as quoted in Titanic: Voices from the Disaster by Stephanie Barczewski, 2002, p. 192). However, the joy of rescue was tempered by the profound grief and despair of those who had lost loved ones. The conditions on board the Carpathia were crowded, and the emotional atmosphere was heavy with sorrow and trauma. The rescued passengers and crew were provided with blankets, food, and medical attention, but the psychological scars of the disaster would remain for a lifetime. In the days following the sinking, several ships were dispatched to the area to search for bodies. Over 300 bodies were recovered, many of which were later identified and returned to their families for burial. The task of identification was arduous, and the sheer scale of the loss left many families in agonizing uncertainty.

|

| James Cameron Titanic´s (1997) |

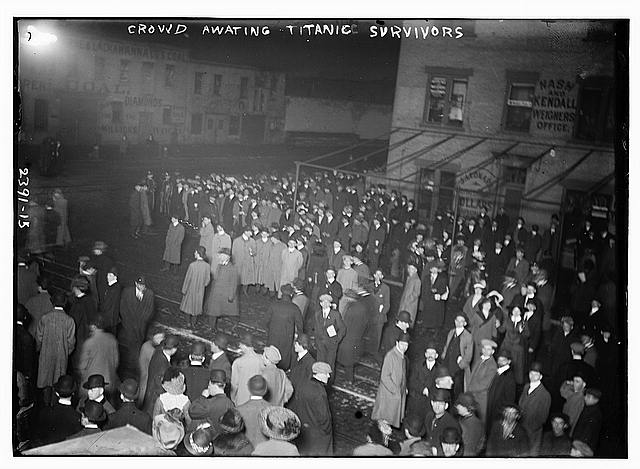

The World Reacts: Shock, Grief, and a Catalyst for Change

The news of the Titanic's sinking sent shockwaves around the globe, dominating newspaper headlines and sparking an unprecedented outpouring of grief and disbelief. The loss of such a magnificent vessel, deemed "unsinkable," shattered public confidence in technological progress and highlighted the vulnerability of human ambition. Memorial services were held in cities around the world, and flags flew at half-mast. The tragedy spurred immediate demands for answers and led to the launch of formal inquiries in both Britain and the United States. The British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry, led by Lord Mersey, and the U.S. Senate Inquiry meticulously examined the circumstances of the sinking, hearing testimony from hundreds of survivors, crew members, and experts. Historians like Wyn Craig Wade in The Titanic: End of a Dream (1979) and Daniel Allen Butler in Unsinkable: The Full Story of the RMS Titanic (1998) have thoroughly analyzed the findings of these inquiries, which revealed critical shortcomings in safety regulations, including the insufficient number of lifeboats, inadequate training for crew in emergency procedures, and the failure to give sufficient weight to ice warnings. The inquiries led to significant and lasting changes in maritime safety laws, most notably the requirement for all ships to carry enough lifeboats for every person on board, the establishment of the International Ice Patrol to monitor ice conditions in the North Atlantic, and the implementation of continuous radio watch on ships at sea.

|

| Crowd awaitinf Titanic Survivors. Photo From the Library of Congress |

Conclusion: A Tragedy That Echoes Through Time

The sinking of the Titanic on that cold April night in 1912 remains a pivotal event in history, a stark reminder of the unpredictable power of nature and the enduring human capacity for both heroism and error. The detailed timeline of the disaster, from the seemingly minor collision to the catastrophic sinking, underscores the speed and finality of the tragedy. The immense human loss, touching countless lives and families, stands as a testament to the profound cost of the disaster. The immediate aftermath, marked by rescue efforts and the subsequent inquiries, not only brought closure for some but also served as a crucial catalyst for significant improvements in maritime safety regulations that continue to protect lives at sea today. The story of the Titanic, "the night the world held its breath," continues to fascinate, to teach, and to evoke a deep sense of empathy for those who were lost and those who survived this unforgettable tragedy.

References

Barczewski, S. (2002). Titanic: Voices from the Disaster. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Barczewski, S. (2004). Titanic: A Night Remembered. Continuum.

Beesley, L. (1912). The Loss of the SS. Titanic: Its Story and Its Lessons. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Butler, D. A. (1998). Unsinkable: The Full Story of the RMS Titanic. Stackpole Books.

Fitch, T., Layton, J. K., & Wormstedt, B. (2015). On a sea of glass: The life & loss of the RMS Titanic (3rd ed.). Amberley Publishing

Halpern, S. (2011). Report into the Loss of the SS. Titanic: A Centennial Reappraisal. The History Press.

Lord, W. (1955). A Night to Remember. Henry Holt and Company.

United Kingdom, Parliament. (1912). Report of the British Wreck Commissioner on the Loss of the Titanic (Cd. 6352). His Majesty's Stationery Office.

United States Senate. (1912). Titanic Disaster: Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Commerce, United States Senate, Sixty-Second Congress, Second Session.

Wade, W. C. (1979). The Titanic: End of a Dream. Penguin Books.

Wilson, A. (2011). Shadow of the Titanic. Simon & Schuster.